Clive Rosendorff 美国西奈山伊坎医学院 James J. Peters退伍军人医疗中心

Clive Rosendorff 美国西奈山伊坎医学院心脏病学教授、和James J. Peters退伍军人医疗中心研究生医学教育主任。现为ACCF/AHA/ASH缺血性心脏病防治中高血压治疗指南修订委员会主席。

大量证据表明,降低升高的血压能降低严重心血管事件风险。大多数指南建议将血压降至140/90 mm Hg以下,但这一目标值在很多情况下较为武断。对此,我们提出以下重要问题:是否应在140/90 mm Hg基础上进一步降低血压?将血压水平降至目前的推荐水平之下能否带来额外获益?有何风险?目前,有关降压目标值的证据主要源自流行病学研究以及评估替代终点和硬终点指标的临床试验。

流行病学研究

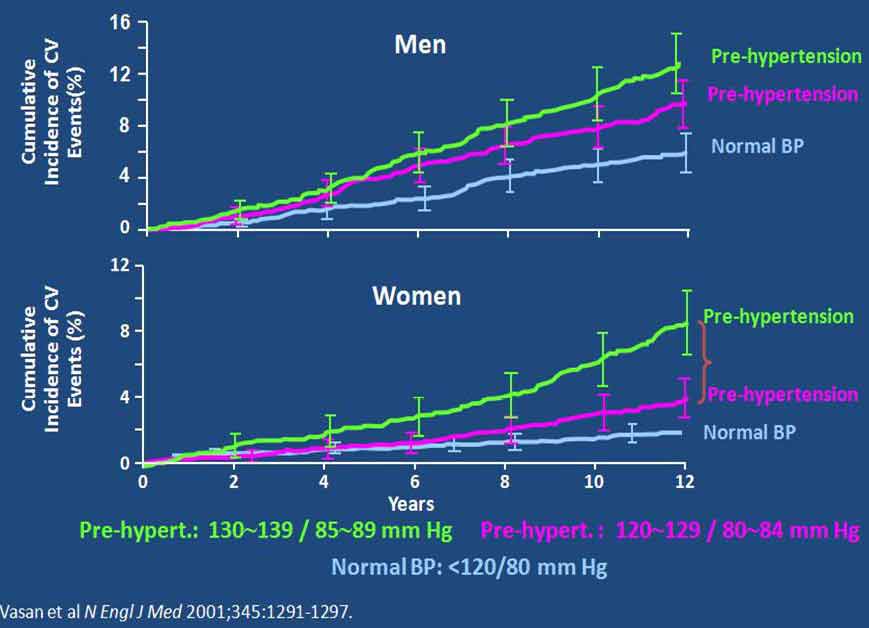

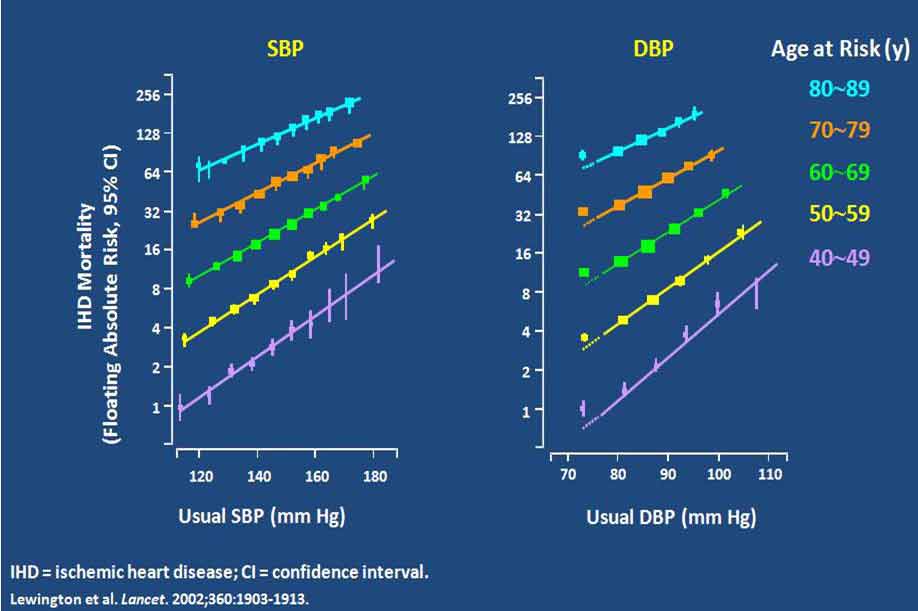

两项研究显示,血压越低,心血管事件累积发生率越低。Framingham研究组报告称,与正常血压相比(<120/80 mm Hg),高血压前期的血压水平(120~139 / 80~89 mm Hg)可增加心血管事件发生率(图1)。Lewington等人开展的一项大型流行病学研究显示,血压降至116/70 mm Hg水平时缺血性心脏病及卒中的死亡率降低(图2)。

图1. 高血压前期对心血管风险的影响

图2. 前瞻性研究显示随血压降低,缺血性心脏病死亡率降低

有替代终点指标的临床试验

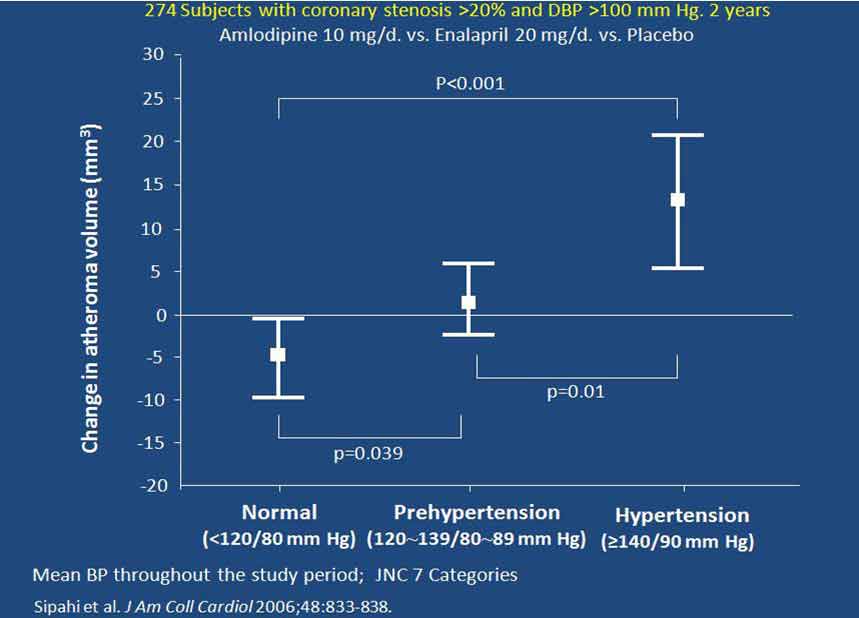

CAMELOT研究中,有274例患者在研究开始及依那普利或氨氯地平降压治疗2年后,采用血管内超声评估冠状动脉(冠脉)粥样斑块体积。结果发现,干预治疗2年后,平均血压仍处于高血压(>140/90 mm Hg)范围者的粥样斑块体积增加,而处于高血压前期(120~129 / 80~89 mm Hg)者的粥样斑块体积无变化,血压降至120/80 mm Hg以下者的粥样斑块体积则显著减小(图3)。

图3. CAMELOT- IVUS亚组研究显示治疗后不同高血压状态的粥样斑块体积改变

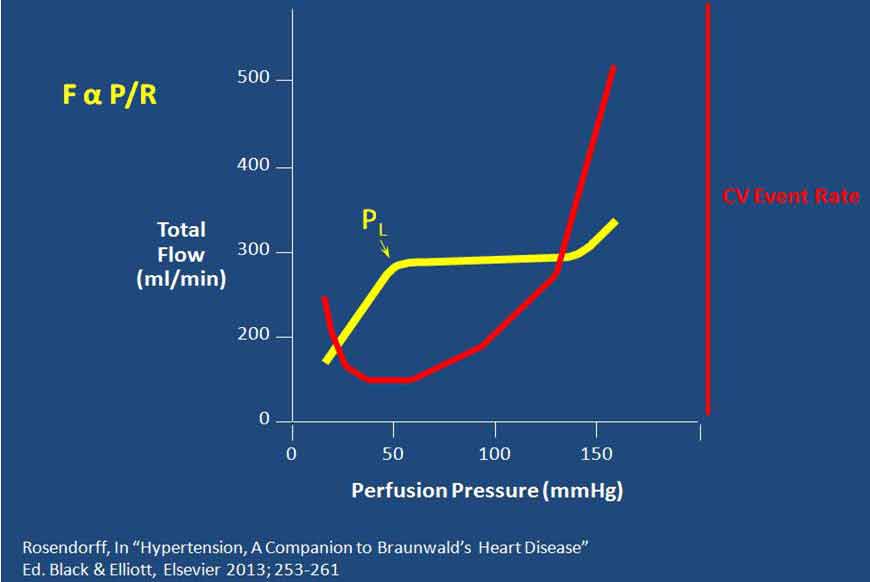

由此提出以下问题:为何不将血压降至120/80 mm Hg以下?若这样做有何潜在危害?解决这一问题的关键在于理解重要器官尤其心脏中血流的自我调节。器官的血流量与灌注压成正比,与血流阻力成反比(FαP/R,如图4所示)。对心肌而言,灌注压就是舒张压,因为几乎所有心肌灌注均发生于舒张期。血压过低时,灌注压会降低,将启动自我调节机制扩张阻力血管,从而降低血流阻力,以使血流量保持不变。当然,血管舒张存在极限,超过这一极限后,若灌注压继续降低将导致血流量下降。因此,可预测当舒张压降低幅度超过冠动自我调节极限时,将会发生心肌缺血甚至心肌梗死(MI)。目前的问题是,我们并不知道对伴有冠脉疾病(可降低心肌氧供)或高血压左心室肥厚(可增加心肌耗氧)的患者而言,其舒张压最低界值是多少。因此,亟需前瞻性临床试验验证是否能设置较低的降压目标值。

图4. 器官的血流量与灌注压成正比,与血流阻力成反比(PL为血压调节的下限)

有硬终点指标的临床试验

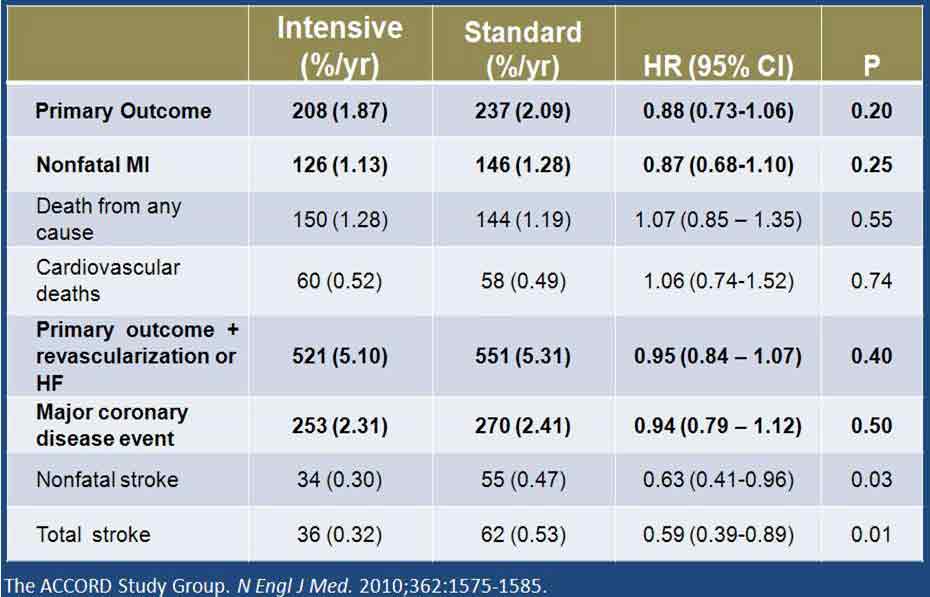

2010年公布的ACCORD(控制糖尿病患者心血管风险行动)研究的血压亚组研究中,受试者被随机分为强化治疗组(降压目标值<120 mm Hg)与常规治疗组(降压目标值为120~139 mm Hg)。研究的主要终点为心血管死亡、MI及卒中的复合终点。中位随访4.7年后,发现标准治疗与强化治疗组的平均收缩压分别为133.5 mm Hg和119.3 mm Hg,差异达14.2 mm Hg。但两组间的主要终点或心血管死亡和MI发生率并无显著差异(图5)。与标准治疗组相比,强化治疗组患者仅有较小的有统计学差异的卒中获益。因此,ACCORD研究者总结,研究结果未能为“强化血压控制降低主要心血管事件复合终点提供证据支持”。

但对上述结果也有不同的解读。其中,大家比较感兴趣的是随访最后4年强化治疗组的平均舒张压为60~65 mm Hg。从冠脉自我调节下限的角度来说,我们需确定的不是“强化治疗是否有益”,而是“强化治疗是否有害”,即在上述较低舒张压水平时,患者的心血管事件发生风险是否会增加。从ACCORD研究结果来看,答案很明确为否定性的。实际上,与常规治疗组相比,强化治疗组主要终点、非致死性MI、严重冠脉疾病发生率均较低,但未达显著统计学差异。此外,强化治疗组的卒中风险有所降低,且有显著统计学意义(图5)。

图5. ACCORD研究的主要和次要结果

结论

综上所述,是否意味着所有高血压患者都应将目标血压降至<120/80 mm Hg?就卒中预防而言,证据相对确凿,卒中高危患者可考虑选择较低的降压目标值。冠脉疾病高危患者(包括糖尿病患者)或冠脉疾病患者,可能也是积极强化降压治疗的适宜人群。其他患者可继续选用既往<140/90 mm Hg的降压目标值。

There is abundant evidence that lowering an elevated blood pressure (BP) reduces the risk of serious cardiovascular events. Most guidelines suggest lowering BP to <140/90 mm Hg. In many ways, this cut-off value is very arbitrary. Important questions are: Should we go lower than that? Are there benefits in lowering the BP to levels lower than those currently recommended? What are the risks?

The evidence for lower BP targets is epidemiologic studies, clinical trials with surrogate outcome measures, and clinical trials with hard outcome measures.

Epidemiologic Studies:

Two studies have shown that the lower the BP the less is the cumulative incidence of CV events. The Framingham research group [1] reported that even “pre-hypertension” levels of BP (120-139/80-89 mm Hg) had a higher CV event rate than “normal” BP (<120/<80 mm Hg) (Fig 1.). In a very large epidemiology study, Lewington et al. [2] showed that ischemic heart disease (and stroke) mortality declined with BPs right down to about 116/70 mm Hg. (Fig. 2)

Clinical Trials with Surrogate Outcome Measures:

As part of the CAMELOT study 274 patients had intravascular ultrasound measurement [3] of the volume of their coronary atheroma at the start of the study and again after 2 years on either enalapril or amlodipine for their hypertension. Those with a mean BP in the hypertension range (>14/90 mm Hg) had an increase in atheroma volume, those with a mean BP in the “pre-hypertension” range (120-129/80-89 mm Hg) had no change in atheroma volume, while those with a BP lower than 120/80 showed significant regression of atheroma volume. (Fig. 3)

The question is then: Why not lower BP to <120/<80 mm Hg? Is there any potential harm in doing so? The key to answering this question lies in an understanding of the autoregulation of blood flow through vital organs, particularly the myocardium.

Organ blood flow is proportional to perfusion pressure and inversely proportional to resistance (FαP/R). (Fig. 4). In the case of the myocardium P is the diastolic blood pressure (DBP) because nearly all of myocardial perfusion occurs during diastole. If P falls (as would happen with lower and lower BPs), then autoregulatory mechanisms are activated to dilate resistance vessels, thereby decreasing R, so that flow remains constant. Obviously there is a limit to the degree to which vessels can dilate, so that further lowering beyond that limit of P results in a fall in F. It could therefore be predicted that, at DBPs below the lower limit of coronary autoregulaton, there will be myocardial ischemia or even infarction. The problem is that we do not know what that DBP value is in humans, who may also have coronary artery disease (which may decrease myocardial oxygen supply) or hypertension with left ventricular hypertrophy (which will increase myocardial oxygen demand). Therefore, lower BP targets needed to be tested by a prospective clinical trial.

Clinical trials with hard outcome measures:

Such a trial was the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD), published in 2010. In the BP component of ACCORD [4], subjects were randomized to systolic BP (SBP) targets of 120-139 mm Hg. (standard therapy) or <120 mm Hg (intensive therapy). The primary outcome measure was a composite of CV death, myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke. After a mean follow up of 4.7 years, the mean SBP in the standard and intensive groups were 133.5 and 119.3 mm Hg respectively, a difference of 14.2 mm Hg. The results were totally unexpected: there was no significant difference between the two groups for the primary outcome measure, or for CV death or MI (Fig. 5). There was a small but statistically significant benefit of the intensive therapy for stroke. This led the ACCORD investigators to conclude: “The results provide no evidence that the strategy of intensive BP control reduces the rate of a composite of major CV events in such patients”.

However, a different interpretation can be placed on these data. What is of particular interest is that the mean DBP in the intensive group was 60-65 mm Hg over the last 4 years of follow-up. Therefore, in terms of the lower limit of coronary autoregulation discussed above, the right question may not be “is intensive therapy beneficial?” but rather “is intensive therapy harmful?”, that is, was there an increased risk of CV events at these low DBPs? The answer, from ACCORD, is clearly no; in fact the incidence of the primary outcome, of non-fatal MI, and of a major coronary artery disease event was lower in the intensive group, but did not reach statistical significance. In addition, stroke was reduced in the intensive group, and this was statistically significant (Fig. 5).

Conclusion:

Does this mean that we should aim for <120/80 mm Hg in all our hypertensive patients? The evidence for stroke prevention is fairly solid, so that a patient who is felt to be at particular risk for stroke may be seriously considered to be appropriate for the lower BP target. A patient with coronary artery disease, or with a high risk of coronary artery disease (including those with diabetes), may also be a suitable candidate for more intensive BP lowering. For all others the traditional <140/90 mm Hg target is acceptable [5].

References:

1. Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, et al. Impact of high normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1291-1297.

2. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913.

3. Sipahi I, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, et al. Effects of normal, pre-hypertensive, and hypertensive blood pressure levels on progression of coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:833-838.

4. The ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010:362:1575-1585.

5. Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, et al. AHA Scientific Statement. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease. Circulation 2007;115:2761-2788.

老老年高血压患者的血压目标管理

Wilbert S Aronow 美国韦斯切斯特医学中心/纽约医学院

ACCF/AHA于2011 年与其他多个学会基于前瞻性临床试验数据,联合发表的高血压共识指出,年龄<80岁的高血压患者应将血压降至140/90 mm Hg以下以减少心血管事件发生。根据老老年患者高血压试验(HYVET)研究结果,ACCF/AHA 2011指南推荐,≥80岁患者如能耐受应尽可能将收缩压降至140~145 mm Hg。

HYVET研究是目前在年龄≥80岁人群中开展的唯一一项前瞻性、长期、随机、双盲和安慰剂对照降压研究,入选3845例年龄≥80岁、收缩压≥160 mm Hg的患者(平均年龄为83.6岁,女性占61%,合并心血管疾病者占12%),将其随机分为吲达帕胺加培哚普利组与双盲安慰剂组,平均随访1.8年。目标血压为150/80 mm Hg,治疗后达到的最低收缩压为143 mm Hg。随访第2年时,与基线相比,安慰剂组与治疗组的坐位血压分别降低14.5/6.8 mm Hg和29.5/12.9 mm Hg,立位血压分别降低13.6/7.0 mm Hg和28.3/12.4 mm Hg。

随机分配至降压药物治疗组的患者致死性/非致死性卒中、致死性卒中、全因死亡、心血管死亡及心力衰竭的发生风险分别降低30%(P=0.06)、30%(P=0.05)、21%(P=0.02)、23%(P=0.06)和64%(P<0.001)。因全因死亡率显著降低21%,故数据与安全监测委员会停止了该研究。

HYVET研究的结果支持将接受降压药物治疗的≥80岁老人的目标血压设为150/80 mm Hg。研究中,48%的患者能达该目标血压。高血压患者的心血管疾病患病率较高,因此,药物治疗有望能显著降低其心血管事件。

HYVET 研究并未提供≥80岁体弱患者降压药物应用的相关数据。观察性研究及流行病学数据无法替代随机临床试验,不能用于推荐血压目标值的设定。HYVET研究并未阐明≥80岁老年患者的收缩压是否应降至140 mm Hg以下,也未解答降压治疗最佳目标舒张压。亟需进一步临床试验确定生活方式干预、各种降压药物及其他介入治疗措施对≥80岁老年患者的血压控制疗效及最佳血压控制目标值。

The ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in elderly, developed in collaboration with several key American and/or European groups* recommended on the basis of prospective clinical trial data that the blood pressure should be lowered to less than 140/90 mm Hg in adults younger than 80 years of age to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events. On the basis of data from the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET), the only prospective, long-term, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled antihypertensive study in adults aged 80 years and older, the ACCF/AHA 2011 guidelines recommended lowering the systolic blood pressure to 140~145 mm Hg if tolerated in adults aged 80 years and older.

HYVET included 3,845 patients (61% women) aged 80 years and older, with a mean age of 83.6 years, systolic pressure of 160 mm Hg or higher who were randomized to indapamide plus perindopril, if needed, versus double-blind placebo. Only 12% of the patients had cardiovascular disease. The target blood pressure was 150/80 mm Hg, and the lowest systolic blood pressure reached was 143 mm Hg. Median follow-up was 1.8 years. At 2 years, compared with baseline, the blood pressure while the patient was seated was 14.5/6.8 mm Hg lower on placebo and 29.5/12.9 mm Hg on drug therapy, and standing blood pressure was 13.6/7.0 mm Hg lower on placebo and 28.3/12.4 mm Hg on drug therapy.

Those randomized to anti-hypertensive drug therapy showed a 30% reduction in fatal or nonfatal stroke (P=0.06), 30% reduction in fatal stroke (P=0.05), 21% reduction in all-cause mortality (P=0.02), 23% reduction in cardiovascular death (P=0.06), and 64% reduction in heart failure (P<0.001). The 21% significant reduction in all-cause mortality was the reason the Data and Safety Monitoring Board stopped the study.

The results from HYVET support a target blood pressure of 150/80 mm Hg in octogenarians receiving antihypertensive drug therapy. Target blood pressure was reached in 48% of those patients. Hypertensive patients with a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease would be expected to have a greater absolute reduction in cardiovascular events from drug therapy.

HYVET did not give us data on the use of antihypertensive drugs in frail octogenarians. Observational and epidemiological data are no substitute for randomized clinical trials and cannot be used to recommend blood pressure goals. HYVET did not answer the question whether the systolic blood pressure should be lowered below 140 mm Hg nor did it identify optimal diastolic blood pressure targets for octogenarians should be. Clinical trial data are needed to determine the efficacy of lifestyle measures, different types of antihypertensive drugs, and other interventional approaches to control hypertension in patients aged 80 years and older as well as the optimal blood pressure goal.

* the American Academy of Neurology, the American Geriatrics Society, the American Society for Preventive Cardiology, the American Society of Hypertension, the American Society of Nephrology, the Association of Black Cardiologists, and the European Society of Hypertension.

[下一页] [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]